Believing secession was eminent, on Dec. 10 South Carolina’s congressmen met with President James Buchanan, demanding he surrender the forts and arsenal once the secession was announced. While Buchanan didn’t want to start a civil war during his final days in office, he also was unwilling to hand over the forts. In trying to find a way out of this sticky situation, Buchanan assured the South Carolinians that he would not reinforce Charleston’s forts until a peaceful transfer of the properties could be arranged, in return for the Carolinians’ promise that they would not attack the forts until those agreements had been successfully concluded.

Major Robert Anderson, photo by Mathew Brady

Anderson with his wife, Eliza Bayard Anderson, and son, Robert Jr.

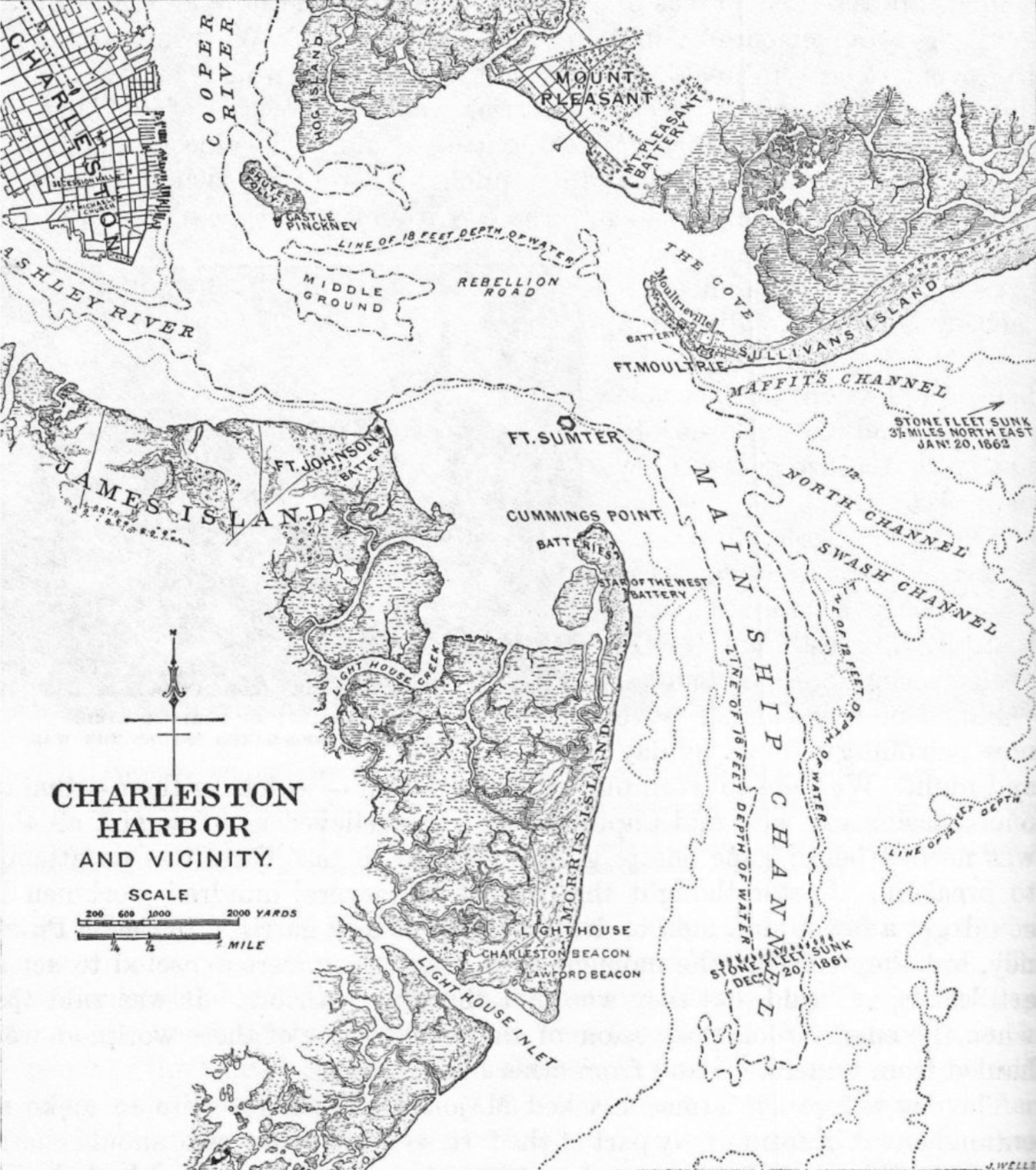

By the dark night of Dec. 26, Anderson and his men had packed up everything they could and boarded several schooners en route to Fort Sumter. Capt. Abner Doubleday, the man now generally – though perhaps incorrectly – credited with inventing the game of baseball, wrote: “Anderson approached me as I advanced, and said quietly, “I have determined to evacuate this post immediately, for the purpose of occupying Fort Sumter; I can only allow you twenty minutes to form your company and be in readiness to start.” I was surprised at this announcement, and realized the gravity of the situation at a glance.”

Captain, later Major General Abner Doubleday

Robert Anderson's telegram announcing the surrender of Fort Sumter

President Buchanan seemed shaken by news of the move as well and called his cabinet together to discuss their options on Dec. 27, the same day Charleston militia rowed out to seize the small detachment of several officers and civilians at Castle Pinckney and the now- abandoned Fort Moultrie. The next day, Buchanan announced Washington’s refusal to surrender Fort Sumter. The die had been cast. Everyone held their breath awaiting what might come next.