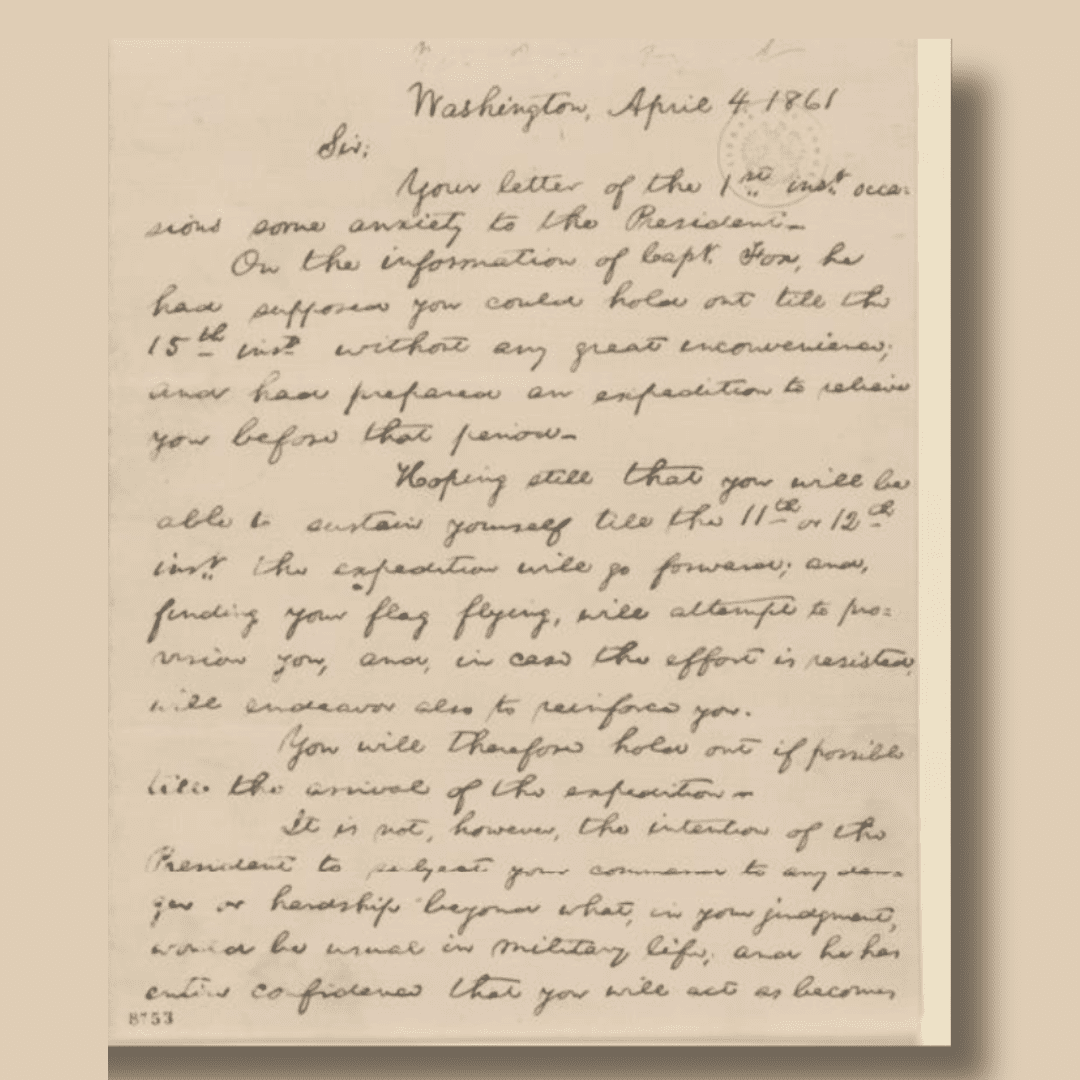

In a message drafted in his own handwriting, President Lincoln wrote to U.S. Maj. Robert Anderson at Fort Sumter saying: “I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only; and that, if such an attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice.” A copy of the letter was delivered to S.C. Gov. Francis Pickens as well, despite the disapproval of Lincoln’s Cabinet. In A Short History of Charleston, historian Robert Rosen calls the wording of the note “a masterpiece of ambiguity.”

Understanding that all parties would interpret the note differently, Southern historian Charles W. Ramsdell in his 1937 book, Lincoln and Fort Sumter, explains: “To the suspicious and apprehensive Confederates it did not merely give information that provisions would be sent to Anderson’s garrison – which should be enough to bring about an attempt to take the fort – but it carried a threat that force would be used if the provisions were not allowed to be brought in. … To Northern readers the same words meant only that the government was taking food to hungry men to whom it was under special obligation. Northern men would see no threat; they would understand only that their government did not propose to use force if it could be avoided.”

Yet an interesting, last-minute change of plans was taking place on the expedition’s flagship, the Powhatan, a ship that would be critical in successfully delivering supplies to Anderson at Fort Sumter. When the Powhatan left New York the evening of April 6, it was not under Capt. Mercer’s command, but under that of Lt. David D. Porter. Nor was Porter taking the ship to Fort Sumter; he was to deliver the ship to Fort Pickens in Pensacola, FL. The new orders had been made secretly under Lincoln’s personal directive.

Thinking there had been a mix-up and after meeting briefly with the President who did not clear up the “misunderstanding,” Lincoln’s Secretary of War, William H. Seward, sent a telegraph to Lt. Porter commanding him to deliver the Powhatan at once to Capt. Mercer – to which Porter replied: “HAVE RECEIVED CONFIDENTIAL ORDERS FROM THE PRESIDENT AND SHALL OBEY THEM.”

What was going on?

Rosen hypothesizes “… the Confederates already knew from intelligence and even newspaper reports that a large naval expedition was on its way. Theoretically, no one knew the destination of Captain Fox’s ships, but Lincoln’s message had implied that force would be available. It was assumed that Fox’s expedition must be that force. Some of the ships were actually heading to Pensacola, but that fact was kept secret, so secret that the Confederates assumed incorrectly that the entire expedition was headed for Charleston.”

Meanwhile, Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut, wife of Col. James Chesnut, Beauregard’s second in command, wrote in her diary that day: “The plot thickens, the air is red hot with rumors… in spite of all, Tom Huger came for us and we went on the Planter to take a look at Morris Island…”

As Mary and her friends enjoy a lovely spring day perusing the Morris Island batteries, we’ll pause our narrative for today.