The HL Hunley was the first combat submarine to successfully sink an enemy warship. But it took some trial and error to reach this historic event. The Hunley’s journey was marked by innovation, courage, and tragedy. The story of the Hunley has spanned centuries and become one of the most mysterious events in recent maritime history. The Hunley’s story begins even before her construction, as early as April 1861.

President Abraham Lincoln ordered United States forces to begin blockading major Confederate ports along the coastline of the southern half of the country. The idea was to close all Confederate ports, preventing the export of goods that supported the Confederate economy and preventing delivery of supplies to the Confederate States of America. This strategy for the United States would become very effective. Covering 3,500 miles of coastline and 12 major ports, the Federal blockade began to choke off the supply lines to the Confederacy. This would cause the Confederate States of America to slowly starve, their government was desperate for a way to break the blockade and bring in those much-needed supplies.

Up against the might of the United States Navy, the Confederacy was forced to be creative in coming up with a solution that might help them break through the barricades preventing them from receiving supplies. As they could not fight the ships with their own vessels above water, thoughts turned to slipping underneath the barricade. Rethinking traditional naval battle tactics is where The Hunley’s story truly begins.

Horace Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson were the minds behind the Hunley, but it was not their first attempt at creating a machine that could dive underneath the waters and the United States Navy’s blockade. Prior to creating the Hunley, these men built several other experimental underwater vessels and helped kickstart the age of the submarine. Together, these three men would develop two early prototypes, the Pioneer, and the American Diver. All three boats would be financially backed by Horace Hunley.

The Pioneer was the first vessel built by Hunley, McClintock and Watson. It was thirty feet long and 4 feet in diameter. The crew consisted of 2 members, one to pilot the vessel and the other to manually rotate the propeller. The Pioneer was equipped with an explosive device that could be attached to enemy ships and blown up with a clockwork mechanism. This first of the three submarines performed fairly well. After testing it in the Mississippi River in the early winter of 1862, the Confederates moved it to New Orleans where it successfully sunk a schooner on Lake Pontchartrain during additional trials. Unfortunately for the Pioneer, United States troops were on the march towards New Orleans, and rather than take the submersible with them, the three inventors were forced to scuttle it and leave it behind in the New Canal Basin in April of 1862.

Hunley, Watson, and McClintock would take blueprints, diagrams, and drawings and flee to Mobile, Alabama. Once there, they would begin work on the 2nd of their two submarines, the Pioneer II, or American Diver as it became known. Soon after arriving in Mobile, the three inventors teamed up with a pair of owners of a machine shop, Thomas Park, and Thomas Lyons. Together, the five men would work on developing a second submarine to test in the Alabama waters. Additionally, at this time, the project would start to receive local military support. One of the main engineers or builders on the project was Lieutenant William A. Alexander of the 21st Alabama Volunteer Regiment. After the war, Alexander stated that he was assisted by another member of the 21st Alabama, George E. Dixon. Dixon’s involvement with the American Diver would place him on the path to become an integral part of the Hunley’s story. But he was first assigned to assist with work on the American Diver.

This new sub would be 36 feet long, 3 feet wide, and 4 feet high. According to McClintock, this submarine was “built tapering or molded, to make it easy to pass through the water.” In fact, the American Diver, as an improvement upon the Pioneer, would serve as the template for the Hunley. It would require some improvements itself though as the American Diver would ultimately be unsuccessful.

The group of engineers for the American Diver made several attempts to build first an electromagnetic engine and then a steam engine. Both attempts were costly and ultimately failed. These engines could not produce enough power to propel the submarine efficiently and safely. McClintock then fitted cranks that could turn the propeller by hand, utilizing 4 men at a time. Although this meant that the American Diver was ready for harbor trials in January of 1863, it was still not able to make it useful against the United States Navy blockade. In fact, McClintock himself said, “unable to get a speed sufficient to make the boat of service against the vessels blockading the port.”

Despite these limitations, the Confederates thought that they would still give American Diver a try, foreshadowing their persistence with the HL Hunley. Sometime in February of 1863, the submarine was towed down Mobile Bay to Fort Morgan to attempt an attack on the blockading vessels. The attack was unsuccessful. A second attack was planned but American Diver was swamped by foul weather and rough seas. The second submarine built by Confederate engineers had failed, without loss of life, something that would change as they forged ahead. Today, the whereabouts of American Diver are unknown, her rusting hull may still sit under the shifting sands of Mobile Bay, lost to history.

That brings us to the third and final submarine built by the Confederates, the HL Hunley. Watson, McClintock, and Hunley did not linger over the loss of American Diver, they went straight back to planning, confident that they could create an underwater vessel that would break the blockade. Taking lessons that they learned from the failures of Pioneer and American Diver, work on the Hunley began soon after the loss of American Diver in February of 1863. In the early stages, the Hunley was not yet called the Hunley and would be known as the “Fish Boat” or the “Fish Torpedo Boat” or even sometimes, the “Porpoise”, likely due to the streamlined design of the vessel’s body. Over the course of the next 5 months, the Hunley would be constructed, once again improving upon the plans of the submarines that had come before. Initially, the idea was that the Hunley would be designed to dive below its target while towing a floating torpedo behind it on a 200-foot tether. Once the submarine had passed underneath the keel of its target, the torpedo would impact the hull of the ship on the other side and cause an explosion. It was hoped that this explosion would be strong enough to sink whatever target the Hunley set its sights on. To make this dive safely, the captain of the Hunley would need to be able to maneuver the 5-foot-tall submarine between the bottom of the enemy vessel and the ocean floor. By the time July of 1863 rolled around, the Hunley’s engineers were satisfied with the submarine’s performance and a demonstration of its capabilities took place for Confederate officials.

Amongst the Confederates watching this display of naval innovation was Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Mobile’s Naval Commandant. After seeing the success of the submarine and the sinking of the barge, he wrote to P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Confederate forces in the key port of Charleston. Buchanan wrote to Beauregard saying, “I am fully satisfied [the Hunley] can be used successfully in blowing up one or more of the enemy’s Iron Clads in your harbor.” The suggestion of transferring the submarine to the more tranquil waters of Charleston harbor was welcomed with genuine enthusiasm by the designers in Mobile. Perhaps, at last, their invention would have the opportunity to display its attacking capabilities against an enemy warship.

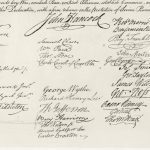

Two of the inventors traveled to Charleston to meet with General Beauregard and deliver the letter from Admiral Franklin praising the capabilities of the submarine. They also showed Beauregard diagrams of the Hunley and explained its operation to him. General Beauregard wasted little time and approved the requested transfer of the “much needed” fish boat. The submarine was to be sent at once to Charleston in the hopes of breaking the blockade. The Hunley was loaded onto two flat rail cars, covered in tarps, to make the secret journey from Mobile to Charleston.

On the morning of August 10, 1863, the journey began. In a cloud of steam and black smoke, the train with its precious cargo pulled out of the railyard. The group of men riding in the passenger car behind the shrouded Hunley said goodbye to Mobile and looked forward with anxious anticipation to the besieged city of Charleston. Two days later, on August 12, the “little submarine” arrived in Charleston. James McClintock and Gus Whitney, one of the builders of the sub, immediately began testing it in the waters of Charleston Harbor.

But for the Confederates, the pace of McClintock and Whitney was too slow. They seized the Hunley and turned it over to Lt. John Payne, a Confederate Navy man with the CSS Chicora. Perhaps this was a mistake as the Hunley began to experience mishaps soon after. On August 29, 1863, the Hunley was moored at Fort Johnson, preparing to make its first attack on the naval blockade in Charleston Harbor, when it sank at the dock. The true story of what happened is really known, there were several conflicting stories at the time. Some witnesses claimed that the wake of a passing ship flooded the open hatches causing the submarine to fill with water and sink. Others claimed that the mooring lines of another ship became entangled on the submarine, pulling it on its side until the hatches were underwater. Whatever the true story is, the result was still the same. The Hunley sank for the first time. Five of her eight crew members were killed when she went down. Lt. James Payne was standing on top of the sub and was able to jump into the water and be rescued. William Robinson escaped through the aft hatch and Charles Hasker, who was trapped by the hatch cover, was able to ride the submarine to the bottom of the harbor before freeing himself and swimming to the surface.

It took several weeks to retrieve the Hunley from the floor of the Charleston Harbor. During this time, Horace Hunley had made his way to Charleston from Mobile and demanded that the submarine be returned to his care. General Beauregard granted the request and Hunley sent for a crew from the machine shop in Mobile to join him in Charleston. Approximately a month and a half after the first sinking of the Hunley, Horace Hunley scheduled a demonstration of its capabilities in October of 1863. He announced that his vessel would dive beneath the CSS Indian Chief and surface on the other side. The submarine began its dive and disappeared beneath the waves. But it did not surface on the other side of the Confederate ship. In fact, it wasn’t seen again for weeks. Bad weather delayed the search efforts and divers were not able to recover the Hunley until November 7, 1863. The submarine was found deep in the harbor channel with its bow deep in the mud and its stern floating. All the souls on board were lost including Horace L Hunley who had captained the boat on its second trial.

When the hatches were opened upon its recovery, witnesses were met with a gruesome sight. The crew members were seemingly frozen in time. Thomas Park was found with his head in the aft conning tower. Horace Hunley, still clutching a candle, was in the forward conning tower. Rescuers reported the forward ballast tank valve had been left open, allowing the submarine to fill with water. The wrench used to operate the seacock was found on the floor of the submarine leading them to theorize Hunley had either forgotten to close the valve or lost the wrench and was unable to close it. The sub’s keel weights had been partially loosened, which suggested the crew realized they were in danger, but not in time to save themselves. This second tragedy, following so closely on the heels of the first sinking, created quite a stir in Charleston.

United States Navy Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, in command of the blockading US fleet, learned of the submarine from Confederate deserters. In response to this new information, Dahlgren ordered his squadron to anchor in shallow water, hang ropes and chains over the sides of their ships as defensive measures, and deploy picket craft to keep torpedo-bearing boats away. So not only did the Civil War see the beginnings of the submarine age, but these clever defensive tactics were also the genesis of anti-submarine warfare as well. While Dahlgren prepared his boats for attacks by the Confederate submarine, the Confederates themselves had to decide whether it was worth it to put the Hunley back in action.

General Beauregard was very reluctant to put the vessel back into service after the first two sinkings, writing that “it is more dangerous to those who use it than to the enemy.” However, the backers of the submarine were incredibly persuasive. This included Lt. William Alexander and Lt. George Dixon, both of whom believed fiercely that the Hunley had the ability to break the blockade. Yet they both knew that the Hunley would require some modifications if it were to be truly successful. With the United States developing anti-submarine measures, along with the difficulty of controlling the Hunley’s depth and pitch while submerged meant that they had to find a different mode of attack.

The submarine would be modified to accommodate these difficulties. Instead of towing the torpedo behind the vessel as it dived, the engineers went for a more direct approach. A spar with a torpedo attached to the tip was mounted to the lower bow of the submarine. With this design, the thought was that the crew could ram the spar into an enemy vessel and detonate the torpedo either on contact or by using a trigger-pulled device. Although this approach was more direct, with the spar being only 16 feet long, it would leave the crew dangerously close to the explosion of the torpedo. There was little time to test the new attack strategy, General Beauregard was still reluctant to trust the submarine and so made the requirement that if the Hunley was to attack, it must run on the surface and not dive beneath the waves. Given that the submarine had now gathered a reputation for being dangerous, the new crew that would operate the Hunley on her third and final voyage was an all-volunteer crew, led by Lt George Dixon.

From mid-December 1863 through January of 1864, Dixon and his crew would run the Hunley through its paces. Some nights, they got so close to the picket boats that they could hear the US Navy sailors singing. However, they never got close enough to attack. Dixon shared his frustration with a friend in a letter, writing of the bad weather that prevented them from success “to catch the Atlantic Ocean smooth during the winter months is considerable of an undertaking and one that I never wish to undertake again.” In February of 1864, Dixon got the calm seas that he was hoping for and the crew began to prepare for their ambitious attack. The target? The USS Housatonic. The Housatonic was a sloop of war that had been stationed outside of Charleston with the blockade group since September 1861.

One of the clear facts about the sinking of the Hunley is that her crew were most likely killed immediately at their posts. When the Hunley was recovered and restoration was begun, the researchers discovered the crew members still at their posts with no signs that they had tried to escape the submarine. To this day, we still wonder what happened to the Hunley that would have caused her crew to be found this way. The next part of the job was to try and identify the crew. For most of the crew, this research would take a little work but would lead to the discovery of 19th-century artifacts. Perhaps one of the most interesting of these artifacts was a gold coin inscribed Shiloh April 6th, 1862, My Life Preserver, G.E.D.

After the researchers were able to identify Dixon and the rest of the crew, plans were made to bury them, an event over 100 years in the making. On April 17, 2004, the final crew of the Hunley were laid to rest in Magnolia Cemetery, where they remain today along with others who lost their lives during the tragic tests of the Hunley. The development of the Hunley began the era of submarine warfare, however, it would take a long time before the United States Navy would add submarines to its fleet. It wouldn’t be until 1900 that the US Navy would purchase its first submarine, the USS Holland, named for its inventor.

While the Hunley was a model of naval innovation, it was also a source of considerable misfortune. Twenty-one men died in its service, in a failed attempt to break the United States’ blockade of Charleston Harbor. Though the Hunley was successful in sinking the Housatonic, that was its only success. Though its creation changed naval warfare forever, its sinking remains one of the most notable mysteries in naval history today.